The Future of HCI: Designing the bridge between people and machines

- Chris Burgess

- Oct 31, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2025

Computing is stepping out from the screen and into the world around us. The challenge ahead is to help humans and computers evolve together so that the future feels natural, usable, and human.

TLDR

Spatial computing is the next major shift in how humans engage with technology. The premise is that computers are becoming spatially aware of the world in which they exist. This means that instead of interacting through flat screens, we will soon experience computing in three dimensions — information that lives around us, responds to our gaze, and blends into physical space.

This shift raises an urgent design question: how do we build human-computer interaction (HCI) that makes this transition natural, valuable, and intuitive?

I first delivered this topic as a lecture at Technological University Dublin in November 2024. Since then, I have updated it to reflect new developments in this fast-moving field.

This post is structured around the three core components of HCI: humans, computers, and interaction. Each section explores one in turn, showing how they connect and build on one another to shape the future of spatial computing.

Humans: adoption depends on value, ease, and familiarity. People try new technology when it delivers an immediate benefit and takes little effort to learn.

Computers: computing is entering a 3D era, but devices are still maturing. Apple, Meta, and Google are defining the platforms that will normalise spatial interfaces.

Interaction: the future of input will rely on hands, eyes, and subtle haptics. Pinches, gaze, and wrist-based feedback will make spatial computing feel more intuitive.

The lesson is simple. Spatial computing will only become mainstream when HCI feels human first. Technology must offer clear value, use natural gestures, and appear in forms people are proud to wear.

If you prefer to watch or listen, you can find the recorded lecture here: https://link.crwburgess.com/future-of-hci-video.

Humans: Who are we, and what do we need?

Computing did not become mainstream until the 1990s. As a result, adoption has been largely shaped by how old you were and what line of work you were in at that moment. Builders and Boomers were typically in the latter stages of their careers, so less likely to adopt computing deeply. Gen X were earlier in their careers and more open to experimentation. Gen Y grew up with computers, so familiarity came naturally. Gen Z experienced rapid leaps in design and usability, driven by the smartphone. And Gen Alpha seem to use machines effortlessly, even from an early age.

User experience (UX) has evolved, but it often assumes a base level of digital familiarity that is no longer universal. Take the hamburger menu, for example. It has become a standard feature across websites and mobile apps, yet it is not something all generations naturally associate with opening a menu. For those who did not grow up with modern operating systems, that small design choice adds friction. As interfaces build on existing conventions rather than reintroducing them, the barrier to entry for older generations grows, and adoption becomes less likely.

Spatial computing will face the same challenge, only amplified. The people most likely to adopt and shape it are Gen Y onwards, with Gen X following close behind. But the design language that will define spatial computing belongs to Gen Alpha. They will expect computing to be spatial by default, not as an evolution of screens. The best approach is to design for how Gen Alpha will use it, then work backwards to make those interactions legible to older generations. This way, spatial UX becomes future-native while remaining inclusive for today’s users.

People adopt technology when it makes life easier and feels familiar. For spatial computing, the opportunity lies with the generations who already think in 3D. Designing with them in mind, then working backward, will define how computing evolves from here.

Computers: How have they evolved and where are they going?

For decades, computing has evolved in two dimensions. Each generation, from the desktop, laptop, tablet, phone, has refined what came before. The next leap is not another rectangle. It is a shift into space.

This section takes a Western-centric view and focuses on three companies that are shaping how humans will understand and ultimately adopt spatial computing.

Apple

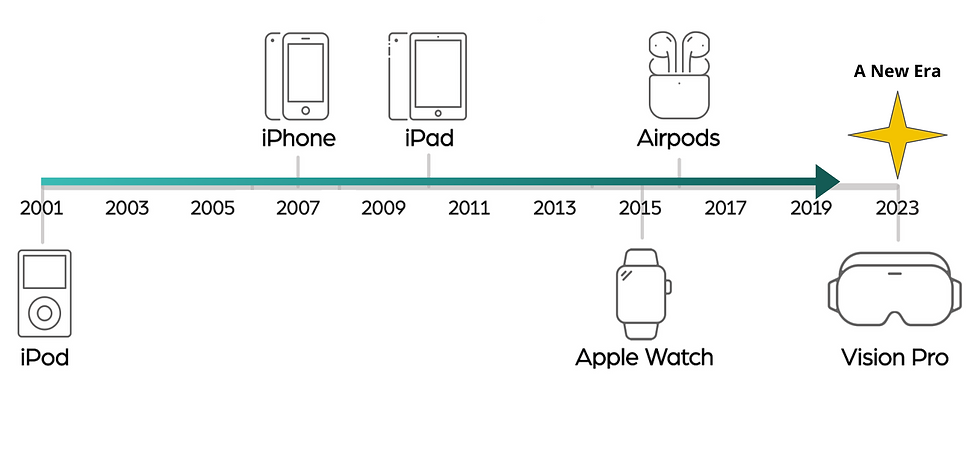

Apple has long been seen as the company of innovation, but I would argue that most of its breakthroughs have been evolutionary rather than revolutionary. The iPod didn’t invent portable music, it refined it. The iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone, but it unified music, telephony, and the internet in a way that made sense to everyone. Even the iPad and Apple Watch built on existing behaviours rather than creating new ones.

The Vision Pro changes that pattern because it is Apple’s first device to move computing from a flat screen into three-dimensional space. What makes it interesting though is that the UX somehow still feels familiar. Apple has carried forward gestures already introduced through the Apple Watch and touchscreen such as pinching and scrolling, and turned them 3D.

That approach is what will make spatial computing usable at scale. By unifying what has come before, Apple is helping people cross the threshold into 3D computing without asking them to relearn everything.

Meta

Meta has been one of the biggest investors in the future of computing and has consistently pushed the boundary of what is possible in this space. The journey began with headsets. The early versions needed to be connected to a computer, then they built standalone devices that ran on battery power, and now they have headsets that use a full colour video feed to allow you to interact with digital content in the real world. Each step has evolved computing as we know it.

More recently, Meta’s focus has shifted toward glasses. Their goal is to achieve lightweight devices that look and feel like something you would wear every day, but that also bring digital content into your field of view.

The Ray-Ban partnership marks the first major step in that direction. In phase one, the glasses were not yet spatial, but they introduced a form factor people actually wanted to wear. The early models focused on cameras, audio, and voice assistance — familiar, simple, and social.

Phase two introduced a heads-up display (HUD). While still limited, it begins to show how more aspects of the smartphone experience can move into eyewear. They also introduced the ability to use your hands to interact which is exciting.

Meta’s Orion project points clearly to the future. It cannot be bought today, but it demonstrates the direction of travel for more immersive lightweight glasses that blend digital and physical worlds seamlessly. The technology behind it is extraordinary, but the cost is prohibitive.

What makes Meta’s story compelling is not its speed but its patience, evolving steadily from headsets to everyday wear in a way that feels natural.

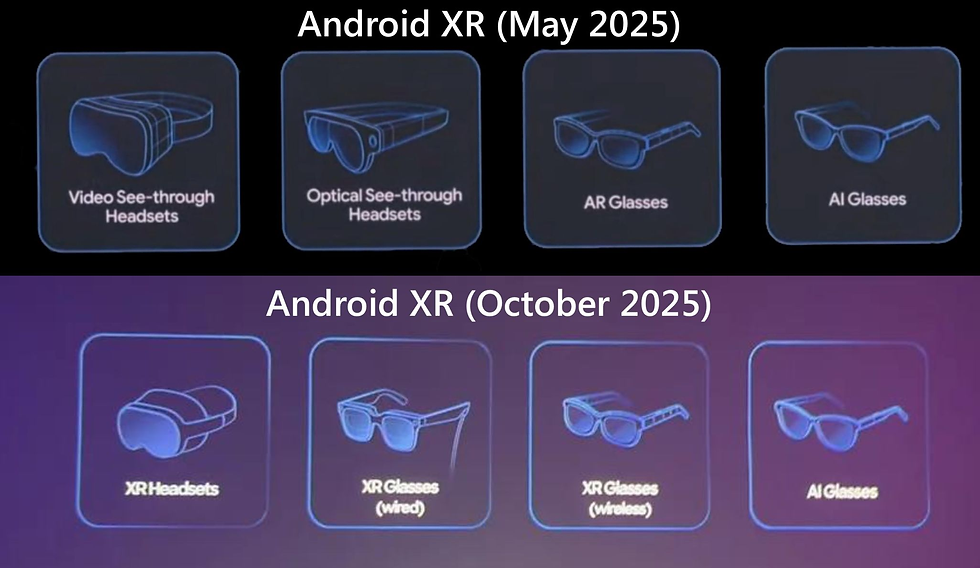

Google’s Android XR platform is the more recent arrival. From the off, rather than focusing on AR versus VR, Google has tried to reframe (no pun intended) the conversation to be about headsets versus glasses. This shift matters because it signal that the industry’s language is starting to stabilise, even if the devices themselves are still early.

For immersive headsets, Google has initially partnered with Samsung on hardware and Qualcomm on chipsets to accelerate adoption, and more hardware partners are expected to follow.

It is collaborating with Magic Leap for its XR glasses offering, and with Kering Eyewear for its AI glasses which will help ensure it achieves fashion and function (and keeps up with the partnership Meta formed with Ray Ban).

In many ways, Google is applying what it knows best: building operating systems that work across a wide range of devices. Android XR extends this thinking. It takes Google’s long history with technologies like ARCore, Lens, Mediapipe, and geospatial APIs and unifies them under one platform. It is translating that experience into a three-dimensional world, bridging from 2D interfaces into 3D environments and creating a foundation for the next generation of hardware makers to build upon.

The future of computing is three-dimensional, but the devices that deliver it are still learning how to disappear. Function and comfort must evolve together before spatial computing can feel as effortless as picking up a phone. What is also clear is that users do not care about technical definitions, they care about what the device is for.

Interaction: How will we use the interfaces of the future?

When most people imagine interacting with content in mid-air, they likely picture what Hollywood has showed them. Minority Report gave us Tom Cruise waving through mid-air displays, but there have been many more examples since. Hollywood has a knack for presenting a convincing vision of the future.

However futuristic those concepts once seemed, they are now becoming a reality.

The way we interact with computers has always evolved alongside their form. It began with the keyboard. Then came the graphical interface, which introduced the mouse — a simple device that turned movement into selection. Gaming brought controllers that added complexity and precision, each new button combination expanding what was possible. Headsets changed ergonomics again, introducing hand-held sensors that eventually recognised individual finger movements.

However, they are still accessories, separate from the computer itself. The touchscreen changed that. Suddenly, our hands became the interface. Touch gestures like swiping, tapping, and pinching are now so intuitive that even young children use them instinctively. Accessories became optional.

Up until this point, what had unified computer interaction was the sense of touch. As computing moves into 3D space, the challenge is to recreate that same intuition while maintaining reliability.

Interacting in mid-air introduces a higher risk of accidental input, which is why the pinch has quietly become the universal gesture. Apple uses it in both the Apple Watch and the Vision Pro. Meta has been using it for a long time, and Google’s Android XR has adopted it too. It works because it is simple and reliable.

Apple has added eye tracking to the pinch, reducing the risk of accidental input to almost zero, and this looks set to become the common standard for interaction.

The next ingredient to consider is haptic feedback. This is the physical confirmation that grounds interaction and gives us confidence we have done something correctly.

Meta’s EMG bands already let users click or scroll while their hands rest naturally at their sides. The addition of gentle wrist-based haptics, a small buzz confirming selection, is the latest attempt to reintroduce that sense of touch.

The next evolution may come from partnerships between major tech players and fashion-led watchmakers. Apple is already synonymous with wearable design, while Meta depends on partnerships to drive adoption. Once it learns more from EMG use in the wild, a watch collaboration seems inevitable.

Interaction design succeeds when it disappears into behaviour. The more natural and reliable it feels, the faster adoption will come. Ultimately, trust built through reliability is what will move spatial computing along the adoption curve toward the early majority, turning experimentation into habit.

What does all this mean for the future of HCI?

Spatial computing is not a distant vision. The core technologies already exist, but HCI and its future adoption will depend on experience design.

Gartner’s Hype Cycle is a useful barometer for where technology sits. As of 2024, spatial computing is at the Innovation Trigger stage. It is still early, but the groundwork must be laid now by keeping a few lessons in mind:

People adopt when value is obvious and effort is low.

Devices win when they balance capability with comfort.

Interaction becomes mainstream when gestures feel human and feedback is felt.

For founders and investors, this is the window to experiment. Build spatial experiences that solve real problems today and design them with the patience to evolve as devices mature.

Spatial computing will not replace screens overnight. It will quietly extend them, reshaping how we see, touch, and share information until the boundary between digital and physical simply dissolves.

Related reading to explore next

If you are leading a startup or scaling a product team and want to turn HCI for spatial computing into measurable outcomes, let’s talk. I help founders and product leaders design spatial experiences that feel natural, credible, and ready for the market. Reach out at info@crwburgess.com.

Comments